Navigating Palliative Care: A qualitative study of the needs and challenges of newly qualified nurses

Camilla Askov MOUSING 1,2 RN, MScN, PhD, Associate Professor https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6662-7584

Anne Tvede PLETH 2 RN, MScN, Associate Professor https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1619-6111

Tinne Bertram FLÆNG 2 RN, Msc Antropology of Health, Assistant Professor.

Janni Dahlgaard GRAVESEN 2 RN, MScN, Associate Professor https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9114-8702

Vibeke Røn NOER 1 RN,MScN, PhD, Associate Professor, Head of Research Programme https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9692-9716

1 Research Centre for Quality of Education, Profession Policy & Practice, Programme for Practice Studies, VIA University College, Aarhus, Denmark.

2 VIA University College, Department of Nursing, Randers, Holstebro and Viborg, Denmark.

Summary

Background: Newly qualified nurses are expected to care for life-threateningly ill patients and their relatives. However, there is currently a significant research gap concerning the experiences and challenges faced by newly qualified Danish nurses when encountering basic palliative care in practice.

Aim: To explore the experiences of newly qualified nurses providing basic palliative care.

Methods: Individual in-depth interviews with nine nurses were conducted, and data analyzed through qualitative, descriptive analysis.

Findings: The study underscores the pivotal shift from being a student to becoming a practicing nurse, revealing uncertainties and a need to engage in palliative care during clinical training. Additionally, the study unveils a pervasive sense of busyness in the practice of healthcare, preventing a balance between efficiency and calmness in palliative care. Administering medication, handling crisis-reactions, and communicating with fearful patients and relatives requires courage and experience. The emotional impact is profound, necessitating support and dialogue. The identified challenges are explored in the discussion, emphasizing how busyness impacts palliative care, and highlighting the significance of structured support mechanisms to enhance newly qualified nurses’ competences and confidence in their work in palliative nursing.

Conclusion: Newly qualified nurses face challenges transitioning to professional practice. The fast-paced healthcare system impedes their ability to deliver sensitive, person-oriented care, causing uncertainty and fear of failure. Ongoing dialogue and support from experienced colleagues are crucial for helping newly qualified nurses prioritize tasks, make informed clinical decisions, and develop leadership skills in basic palliative care.

Keywords: Palliation; Newly qualified nurses; Nursing education; Qualitative research; Healthcare system dynamics; Collegial support

Introduction

This study looks at the experiences of newly qualified nurses performing basic palliation. The purpose of palliative care is to prevent and relieve suffering and support life-threateningly ill patients and their relatives, including ensuring the best quality of life possible during the course of illness (1). Clinically, basic palliative care involves symptom management, psychological and social support, existential and spiritual care, and coordination among healthcare providers to ensure seamless, holistic, and patient-centered care.

Techniques include pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for pain and symptoms, counseling and therapy, social services, advance care planning (ACP), caregiver training and bereavement support (1-3). Patients with life-threatening illnesses, elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, and patients experiencing acute exacerbations of chronic disease require basic palliative care (1; 4).

Basic palliation is provided throughout the healthcare system, including general hospital wards, primary care practices, and in patients’ homes. Integrating basic palliative care into standard healthcare practices presents significant challenges. These challenges, observed in hospitals, general practice, and the primary sector, encompass limited time and resources, inadequate training, delayed identification of palliative care needs, organizational obstacles, and cultural variations in perceptions of illness and death (1; 4).

Prior research has described the need for special skills to work in the palliative field. In particular, the challenges associated with being exposed to human vulnerability, suffering, and death on a daily basis are emphasized (5). Studies highlight the unique blend of clinical skills, emotional resilience, and empathetic communication required to effectively manage the complex needs of palliative care patients. Health professionals must be able to address not only physical symptoms but also the psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions of patient care.

This holistic approach demands a high level of compassion and the ability to support patients and their families through challenging and emotionally charged situations (2-3). Research also emphasizes the importance of training and continuous professional development to equip healthcare providers with the necessary competencies. Effective palliative care relies on the ability to hold delicate end-of-life conversations, manage multidimensional pain, and provide comprehensive, patient-centered care (2; 6). The nurse holds an important role in palliative care (7). Of all healthcare professions, nurses spend the most time with end-of-life patients (8). This places special demands on nurses to be trained and, not least, places high demands on the quality of their education (7; 9).

The development of palliative care in Denmark has significantly evolved over recent decades, transitioning from limited hospice services to being an integrated part of the healthcare system. Timm, Thuesen, and Clark (10) highlight the need for updated undergraduate nursing programs to reflect these clinical advancements. Enhancing educational curricula is essential to preparing nurses for high-quality palliative care, directly impacting patient outcomes and healthcare efficacy.

The Danish National Board of Health, in both 2011 and 2017, emphasized the importance of integrating palliative care concepts and skills (11;1) into relevant foundational education, particularly in healthcare education. In the context of nursing education, a significant change occurred in 2016, where palliation as a concept and phenomenon was first registered (12) in the nursing education reform from that year. The reform focused on preparing future nurses for roles across various healthcare sectors and equipping them to navigate complex situations, including a mandate for palliative care to be included in the training of nurses.

This requirement aims, among other objectives, to align education with the competencies required in a healthcare system characterized by a growing population of individuals living longer with life-threatening illnesses. International research literature shows that nursing students often feel inadequately prepared for palliative care responsibilities (13-16). Students commonly express a lack of knowledge and low confidence in their abilities related to providing basic palliative care (16-17). Danish studies (18-19) have similarly demonstrated that nursing students, both during their studies and in their initial professional practice struggle to navigate the ‘interface between life and death’.

Previous work by the authors of this article has also highlighted the concerns of Danish nursing students about their readiness for palliative care as they transition into their professional roles (20). This lack of confidence in palliative care abilities is a common experience among newly qualified nurses (16; 21). When nurses in palliative care perceive a deficiency in their skills, it can impact the fulfillment of end-of-life wishes for life-threateningly ill patients (22-23). Newly qualified nurses encounter a job market characterized by a plethora of tasks, substantial responsibilities, and constrained staffing. Within this context, they are expected to perform and fulfill their responsibilities, including caring for life-threateningly ill patients and their relatives. There is currently a significant research gap concerning the experiences and challenges faced by newly qualified Danish nurses in basic palliative care. Therefore, this article seeks to elucidate the experiences of newly qualified nurses in their initial two to three years of practice, particularly focusing on their encounters with palliative care.

Method

We conducted semi-structured individual interviews with nurses, who had been in practice for two to three years, all of whom had completed their training in June 2019. These newly qualified nurses had completed their studies as the 2016 curriculum, which included palliative care, was implemented. The life-world interview method by Kvale and Brinkmann (24) served as inspiration for the interview approach, as our aim was to capture the nuanced and complex realities of newly graduated nurses’ experiences with palliative care.

Participants

The research team had previously conducted a study on nursing students’ experiences in learning about palliative care (20). The study involved 174 students with an anticipated final nursing exam in June 2019. Sixty-three of these students consented to be contacted after graduation. We decided to reach out to the newly qualified nurses two years after their graduation. In August 2021, invitations were extended to a third of the 63 new nurses (N=21) to participate in the current study. Invitations were sent to the first 21 individuals on the list, chosen from email addresses without personal information. Depending on participation rates and data richness, additional nurses could be invited until no new information or insights emerged. The invitation email included an information letter and a declaration of consent. All information was reiterated verbally before the interviews commenced, allowing participants the opportunity to provide their consent or withdraw. Nine nurses participated in individual interviews in the Autumn of 2022.

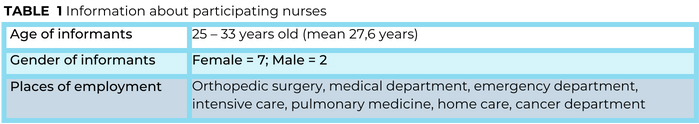

As shown in Table 1, none of the participants had worked in specialized palliative care after graduation.

Data Collection

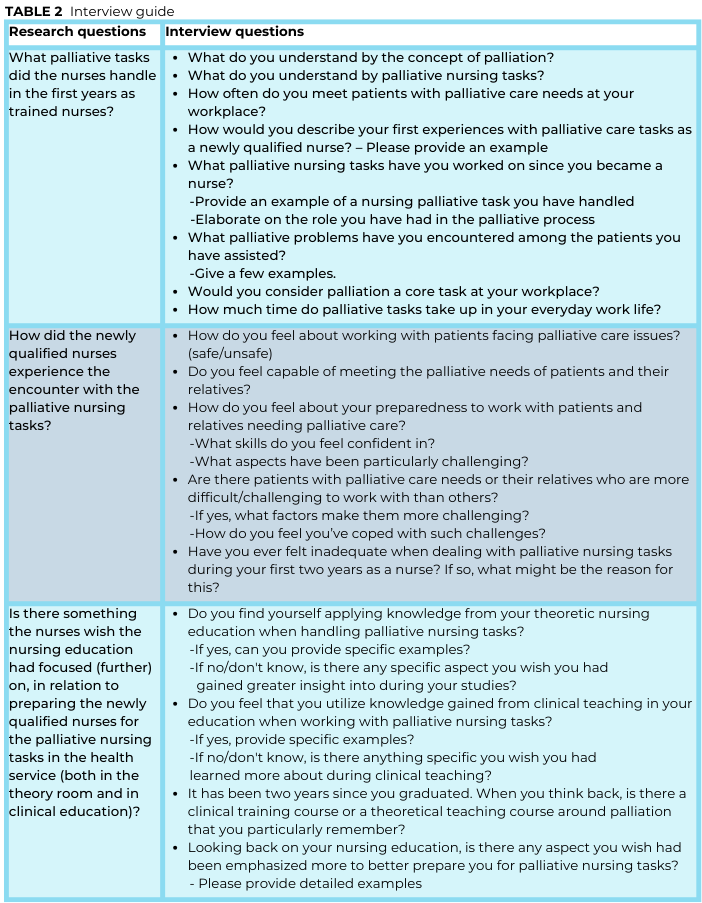

We developed a semi-structured interview guide encompassing the following topics:

1) What palliative tasks did the nurses handle in their initial years as trained nurses?

2) How did the newly qualified nurses experience encounters with palliative nursing tasks?

3) Are there skills, the nurses would like nursing education to have focused on or further emphasized in preparing them for palliative nursing (both in the theoretical room and in clinical education)?

The first topic directly addresses our research question about the practical experiences of newly qualified nurses in palliative care settings. The second topic seeks to capture how engaging in palliative care affects them emotionally and professionally. This aligns with our objective to explore the subjective experiences of nurses in palliative care.

The inclusion of questions related to educational focus (third topic) remains highly relevant for several reasons: contextual understanding; identifying needs and gaps; holistic insight; and implications for practice. So, while the primary aim of the study is to explore the experiences of newly qualified nurses, the educational theme is integral to understanding the broader context of these experiences and identifying actionable insights for improving nursing education and practice.

The interview guide comprised open questions that encouraged the nurses to express themselves in their own words. The interview commenced with some introductory demographic questions and, at the end, participants were invited to ask questions that may have arisen during the interview (Table 2). The interviews were conducted via the digital platform Zoom, influenced by the need for flexibility and accessibility. The built-in recording feature of Zoom facilitated accurate data collection and transcription, enhancing the reliability of our findings. Author two conducted all interviews, which took from 28 to 56 minutes (mean = 44 min).

Analysis

Data was analyzed using qualitative descriptive analysis, following the approach outlined by Sandelowski and conducted in two phases: “Getting a sense of the whole” and “Developing a system” (25). “Getting a sense of the whole” involves immersing ourselves in the data to understand the overall context and the interconnectedness of the participants’ experiences. This process requires reading through the entire dataset multiple times. “Developing a system” refers to the systematic organization and categorization of data to identify patterns and themes. In our study, this involved creating a coding framework that aligns with our research questions and objectives. We adopted the exploratory approach “Storylines, topics, and content”. Data was coded by marking sentences and words related to the research question. This approach allowed us to organize the data in a coherent and meaningful way, facilitating the identification of key themes and insights. The coding process alternated between individual coding alone and collaborative coding. Finally, the codes were synthesized and categorized into overall themes. All authors participated in the analytical process. In our study, a theme represents a central concept or idea that emerges from the data and captures something significant about participants’ experiences in relation to our research questions.

Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and complies with the General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR). All participants were informed, both in writing and orally, about the study’s purpose, voluntary participation, confidentiality, and anonymity. According to Danish law, qualitative studies must be registered only if the project involves the study of human biological material, contains personally identifiable data or is part of a clinical trial. Quotations are included in the presentation of the analysis, with participants anonymized using an assigned ID number.

Results

The newly qualified nurses recognized that palliative care is an essential part of many patient trajectories across different sectors. The nurses described their initial encounters with palliative nursing as uncertain and challenging, expressing that they faced challenging frameworks and constrained conditions for palliative nursing in the healthcare system. There was a general sentiment among the newly qualified nurses that they were not adequately prepared for the palliative care task. Three overall themes of the analysis are presented in figure 1.

The Difficult Transition

The newly qualified nurses felt they had a solid theoretical foundation. However, they expressed a desire for more instruction in palliation during their training:

“Our education was solid, no doubt. We learned a lot of valuable stuff. But it was heavy on theory. It boosted my confidence in that area, but when it came to applying things in the real world, I felt a bit lacking in practical skills, you know?” (X4).

Despite the perception of having a good theoretical foundation, the encounter with palliative care as a newly qualified nurse felt uncertain:

“Yeah, it’s not exactly like free-falling, you know? It’s more like being on this thrilling suspension bridge. You’ve got something to grab onto, so you just got to dive in and figure it out along the way” (X2).

The newly qualified nurses reported that, during their time as students in practice, they had often been shielded from the “difficult part” in their encounters with palliative patients.

They considered it a disadvantage to be shielded from addressing palliative issues, and they expressed a longing for more opportunities for ‘learning spaces’, where they could apply their knowledge and skills related to palliative interventions. It was a stark realization to shoulder the responsibility as recent graduates, particularly since, during their education, they had been either overly protected or closely supervised, making it difficult to get their own experiences:

“So, one shouldn’t be overly sheltered in the very final part of the clinical training, but neither should one be abandoned entirely (…) In one clinical setting, I was entirely on my own, and in the other, I was observed and tested every two minutes. Neither scenario was beneficial” (X2).

The nurses did not feel ready for the meeting with the life-threatening patient in their initial experiences with palliative nursing. As newly qualified nurses, they suddenly find themselves without a guiding hand and are confronted with the challenge of standing alone with limited experience. The nurses highlighted the critical importance of collegial dialogue and support, when having palliative responsibilities as newly qualified nurses. Some had an experienced nurse available for support, while others found a few colleagues to rely on. Some newly qualified nurses however felt a lack of a more formalized introduction to palliative care on the wards, such as a training program or rotation arrangement, which could help when interacting with palliative care patients and their relatives:

“… I really needed a training program in the department (…) I could picture us having a rotation period similar to that of doctors. A period where the emphasis is on palliation” (X2).

A Time-Consuming Effort

Common among the newly qualified nurses was an experience of busyness. They described how the busyness posed challenges when dealing with life-threateningly ill patients and their relatives:

“Well, it’s just hard to find the time for it. It is also difficult to put down your phone and sit down. Well, if you can see it: Now there is not much time left. Sit down and hold a dying person by the hand, if there is no one to do it. Yes. I still find it difficult. When it’s only me there, right to the very end” (X3).

The newly qualified nurses found themselves at a crossroads between efficiency and the need for calm. Busyness was perceived as an inhibiting factor in providing effective palliative care, as the nurses felt compelled to work quickly and efficiently. This left a paradox, especially when there was a clear need for calmness in caring for life-threateningly ill patients:

“I am ready [for the task], but I don’t always feel that there is enough time for it, when patients are in that phase. You must work a little faster and be more efficient, because we have many patients and few staff […]” (X1).

Several newly qualified nurses detailed their strategies for managing the time challenge, such as leaving phones and alarms outside the patient room to establish a tranquil environment conducive to palliative nursing. The absence of defined time frames, and the heightened pressure on the nurses’ capacity to be fully present and offer nursing care for both the patient and their relatives, were emphasized. One of the nurses encapsulated the experience as follows:

“In situations where relatives are on the verge of losing a loved one, and I am tasked with my duties, I must admit that, in my department, there is no time to sit down and engage in profound conversations. Entering a living room with an emotionally charged atmosphere, where people may be grieving, crying, and amidst that, dealing with constant interruptions like phone calls and alarms. Trying to create a space by closing the door and dedicating time for the relatives becomes a complex and demanding task. I believe that aspect is likely the most challenging” (X3).

A recurring theme in the narratives of the newly qualified nurses was a pervasive sense of inadequacy and a constant struggle against time-constraints in their interactions with life-threateningly ill patients and their families. This inadequacy was not a reflection of their professional competence, but rather a consequence of the conditions caused by health-policy priorities, placing the practice of palliative nursing under significant pressure. The nurses acknowledged the challenge of dealing with “…many patients and few hands” (X5), emphasizing the critical nature of this factor. The newly qualified nurses often found themselves unable to enter the ‘palliative care room’ due to a lack of time, resulting in unmet palliative needs for both patients and relatives.

Courage to Face It

The newly qualified nurses’ descriptions of handling palliative care were, independently, marked by fear of making mistakes:

“It wouldn’t be very nice to get on the front page of Ekstra Bladet [Danish newspaper]: ‘My mother was killed by this nurse’ or something” (X1).

The nursing care for life-threateningly ill patients was characterized as demanding and requiring additional effort, recognizing that certain aspects of the care could not be redone. The nurses were deeply affected, and the palliative processes influenced them on both professional and personal levels: “It hit me hard, when I left the patients. And it stayed with me, as I came home” (X2). Frequently, they experienced a sense of inadequacy, incompetence, and powerlessness, expressing feelings of ‘groping around blindly’ or moving like ‘headless chicken’. Many nurses stressed that there is no one-size-fits-all approach in palliative care, highlighting the complexity and uniqueness of each patient’s and relative’s needs.

Overall, the nurses agreed that palliative care require bravery, involving not only the practical aspects, but also the emotional aspects of fully being there. The newly qualified nurses highlighted the significance of handling medications as a vital yet demanding aspect of palliative care. Administering morphine to patients in the terminal phase required intricate professional and personal considerations. Despite the prescription outlining the preparation and dosage, the nurse had to assess the necessity and effectiveness of the medication:

“I find it challenging at times to determine the appropriate dosage and frequency of medication. While there is a prescription, there is also a question of limit: How much can I administer, without it becoming my responsibility? [For the patient’s death] I find that very difficult” (X2).

The newly qualified nurses also found that their communication skills were challenged, when dealing with life-threateningly ill patients and their relatives. The conversations required more than just knowledge of communication theory, and the nurses wished they had more experience and knowledge in handling difficult conversations. The nurses expressed that time and experience were necessary to improve their communication skills in palliative care. A few also mentioned that communicating required courage and this courage could grow as the newly qualified nurses gained more experience:

“Yes, it required a bit of courage. You don’t want to step on anyone’s toes or overstep boundaries. However, I later discovered that perhaps a little courage is all that’s necessary – to dare to have these difficult conversations (…)” (X7).

Nurses found communicating with relatives in palliative care particularly challenging, especially when relatives reacted emotionally, due to unexpected death or difficulty accepting the situation. The newly qualified nurses said they were afraid of being misunderstood, of saying something wrong, which could impact the next of kin’s crisis and/or grief process:

“That was my great frustration for a long time, and what marked the beginning of my quest to improve: How can I get better at this? It involved all the things parents say. How can I respond, without inadvertently reinforcing their feelings or avoiding the issue?” (X4).

Several nurses mentioned that being a young, newly-qualified nurse could pose a challenge in meeting the expectations of patients and relatives, who sought a professional with significant knowledge, experience, and empathy – someone they could rely on during times of crisis and grief.

Discussion

The findings are discussed under the sections ‘Busyness Battles: A Struggle for Balance’ and ‘Accessible Dialogue: Essential Support for Novice Nurses’. Our study focuses on newly qualified nurses, highlighting that effective palliative care requires both time and courage. A key finding is the overwhelming busyness that hinders the delivery of compassionate care. The ‘Busyness Battles’ section calls for systemic changes to support newly qualified nurses. Furthermore, the ‘Accessible Dialogue’ section emphasizes the importance of mentorship and support-systems to bridge the gap between theory and practice. These discussions align with our research aim -to comprehend the experiences of newly qualified nurses within basic palliative care settings.

Busyness Battles: A struggle for Balance

Busyness and the demand for efficiency dominate and shape the daily lives of newly qualified nurses, resulting in the perception of an inability to slow down, detach, or prioritize time to be present in palliative nursing. The challenge of striking a balance between the rapid and efficient nursing care, dictated by the healthcare system, and the sensitive and attentive nursing care required for patients with palliative issues is evident in international literature (26).

The experience of busyness and the overwhelming pressure to work efficiently may stem from a work culture, where busyness prevails. In an environment characterized by busyness, the emphasis is on tasks to be completed and procedures to be carried out, while sensitive presence in challenging circumstances takes a back seat (27). According to the current study, challenges related to prioritizing and gaining experience with sensitive presence in palliative care are not solely due to a lack of knowledge. The newly qualified nurses express feeling theoretically well prepared. However, the challenges are more about the conditions of a busy healthcare system. The opportunities for nurses to explore and be curious about individual patient-needs are constrained by the high work-pace and numerous tasks.

The experience of newly qualified nurses being caught between the healthcare system’s demands for efficiency and the need for calm and presence from patients and relatives, likely reflects a broader challenge beyond palliative care. In this context, Herholdt-Lomholdt raises concerns about a general dissonance between the nursing profession and the system (28). She highlights that an accelerated pace in healthcare, emphasizing speed and productivity, may challenge nurses’ ability to provide situation-specific care. Similarly, Herholdt-Lomholdt draws attention to what she terms ‘procedural work,’ encompassing evidence-based and rule-driven approaches.

Consequently, she raises concerns about the devaluation or neglect of situation-specific nursing care when guidelines and procedures are given precedence in nursing practices. This imbalance may result in dissonance, where administrative processes outweigh individual patient needs. The descriptions provided by newly qualified nurses, indicating a perceived limitation in offering basic palliative nursing care, suggest that they, too, experience this dissonance in their nursing practice.

Martinsen elucidates the implications for nursing and the nurse, when clock time and a busy schedule become dominant:

“When we deal with time based on the clock, we don’t have time, or we have little time, we make use of time, run after time. In a way, the nurse is forced out of time, out of the experienced time with the patient, and then she feels bad. She is left with conflicting expectations from the patient, from the power structures in the care room, and perhaps from colleagues as well” (29 – Author’s translation).

When the nurses, in their initial encounters with patients with palliative care needs, feel the pressure of a busy schedule and sense discord, it can have negative effects on them. Our findings align with Martinsen’s critique of “clock-time,” where the demand for efficiency compromises the quality of patient care. If clock-time dominates the hospital environment, serving as a tool for planning work, and if hospitals are treated like industrial enterprises, where productivity equals value, the joy is taken out of the healthcare environment (29).

Martinsen’s philosophy underscores the need for nurses to use their professional judgment to provide compassionate and individualized care, rather than strictly adhering to procedural and time-based constraints. As demonstrated by our study, the newly qualified nurses may experience feelings of powerlessness, fear of failure, and may consciously or unconsciously choose not to engage in “entering the palliative room.” Other studies have similarly indicated that newly qualified nurses are frustrated because of a lack of experience with palliative situations and limited time for palliative tasks (13).

The individual nurse’s sense of powerlessness and a lack of courage and ability to be present and respond appropriately to the situation, align with findings in Herholdt-Lomholdt’s research (28). When new nurses consciously or unconsciously opt out of ‘entering the palliative care room’, it can be the busyness, noise, and procedures that drown out the patient’s voice, neglecting the person- and situation-specific aspects. However, Herholdt-Lomholdt also stress how nurses may use busyness to hide and protect themselves (28).

Accessible Dialogue: Essential Support for Novice Nurses

The nurses in this study highlight their experience of being shielded during their training, but feeling thrust into palliative care situations upon becoming newly qualified, akin to being “thrown to the lions.” The transition from nursing student to a fully-fledged member of the nursing profession is universally recognized as a challenging and uncertain phase (30-32), marked by the need to navigate a high-paced healthcare system. In addition to adapting to the fast-paced environment, these new nurses must simultaneously develop expertise in palliative nursing.

Our study reveals that the weight of responsibility for providing palliative care significantly affects newly qualified nurses, manifesting as a palpable fear of failure. Newly qualified nurses describe communicating with, establishing relations with, and providing appropriate care to critically ill patients and their families as both challenging and rewarding. Being novices (33) in palliative nursing, they often lack experience in situations, where they are expected to perform and excel.

The nurses in our study highlight collegial dialogue and support as tangible ways to enhance competencies in palliative nursing. They express the need for dialogue with experienced colleagues to navigate the delicate balance between efficiency, adherence to guidelines, and the crucial aspect of sensitive presence. This involves discussions on prioritizing person-oriented and situation-specific nursing care, finding the courage to persevere, and effectively responding to observations and intuitions in the care of life-threateningly ill patients. International studies corroborate that caring for palliative patients is a unique and intricate task that benefits from initiatives such as collegial support from experienced colleagues (21).

Collegial dialogue and support strengthen daily practice (34), and knowledge exchange with seasoned colleagues contributes to the rapid development of professional knowledge and competences in palliative care (26). The idea that support and knowledge-sharing aid in maintaining and developing competences is not novel. Internationally, successful approaches include mentoring and introductory positions for nurses (35-36). Frögéli et al. (30) emphasize that structured interventions can significantly reduce stress and promote well-being among new nurses by encouraging proactive coping strategies and fostering supportive environments. Their research supports our findings, encouraging proactive behaviors such as seeking support, self-care and continuous learning to help newly qualified nurses navigate the complexities of palliative care, reducing feelings of overwhelm and enhancing their competence and confidence.

The need for structured dialogue and support for newly qualified nurses is further reinforced by Berglund et al. (31), who discuss the benefits of transition programs in easing the entry of new nurses into the profession. By fostering a supportive environment, such programs can mitigate stress and promote resilience among new nurses, which is particularly crucial in the demanding field of palliative care. Amidst the heightened pressures within the healthcare system, Denmark has been compelled to explore new strategies and measures to recruit and retain nurses. One such initiative involves the establishment of introductory positions tailored for newly qualified nurses. In Denmark, the formalized creation of introductory positions for nurses is a relatively recent development (37).

Nevertheless, preliminary research findings and experiences with two-year introductory positions suggests, that the crucial aspect from the perspective of new graduates, is finding a balance between being immersed in nursing responsibilities and, concurrently, working in a protective environment. New graduates emphasize that structured support through dialogue, reflection, and supervision offers a sense of security and the opportunity to learn at a suitable pace (38). The general importance of access to dialogues with experienced nurses is evident for new graduates, and this need for collegial support remains essential.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The study’s qualitative design was suitable for gaining in-depth insight into the newly qualified nurses’ encounter with palliative nursing tasks. The virtual nature of Zoom limited our ability to observe non-verbal cues, which are crucial for understanding participants’ emotions and reactions. However, the researcher was able to observe facial expressions and hand/arm gestures. Building trust is more challenging compared to face-to-face interactions, possibly impacting the depth of information shared. Overall, while Zoom interviews provided significant logistical advantages, they also required careful management to maintain the integrity and depth of the data collected. The use of qualitative descriptive analysis (25) has resulted in credible and thorough findings.

Throughout the process, the nurses were very interested in participating in the study, thereby giving a voice to their experiences with palliative care, but the workload after the corona pandemic, as well as a national nurses’ strike that had just ended, made it difficult to plan and conduct the individual interviews. In several cases, interviews had to be canceled on the day due to imposed extra shifts or overtime, and interview times had to be rescheduled. Therefore, data collection took longer than expected. However, we do not believe this had an impact on our study’s results. The similarity in the research teams’ professional backgrounds might limit the diversity of perspectives, potentially overlooking alternative viewpoints. We aimed to mitigate the possible limitations through reflexivity, seeking diverse feedback, and maintaining awareness of our potential biases throughout the research process.

Conclusion

The dialogues with newly qualified nurses highlight aspects related to cultivating the courage and skills necessary for handling palliative nursing tasks within the healthcare system. While these nurses feel theoretically prepared, they express a desire for more active engagement in palliative care during their clinical training. The study indicates that the fast-paced healthcare environment places pressure on nurses, compromising the person-centered care and situation-specific nursing care that is vital in palliative settings. This often results in feelings of insecurity, fear of failure, and inadequacy. The findings also suggest that ongoing dialogue and support from experienced colleagues are crucial for helping newly qualified nurses prioritize tasks, make informed clinical decisions, and develop leadership skills in palliative care.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank the newly qualified nurses who participated in this study for sharing their experiences.

References

1. Sundhedsstyrelsen. Anbefalinger for den palliative indsats. [Internet] 2017 [accessed 22.03.2024] Available at: https://www.sst.dk/da/sygdom-og-behandling/~/media/79CB83AB4DF74C80837BAAAD55347D0D.ashx

2. Connor S, Global Atlas of Palliative Care. 2nd Edition. 2020. Accessed at: whpca_global_atlas_p5_digital_final.pdf (who.int)

3. Timm H, Vittrup R. Mapping and comparison of palliative care nationally and across nations: Denmark as a case in point. Mortality. 2013 May;18(2):116–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576275.2013.786034

4. Bergenholtz H & Jarlbæk L. Basal palliativ indsats på sygehuset – hvorfor, for hvem og hvornår? Omsorg, 2020(3): 5-9.

5. Ingebretsen LP, Sagbakken M. Hospice nurses’ emotional challenges in their encounters with the dying. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being. 2016;11(0130):1–13. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v11.31170

6. WHO. Integrating palliative care and symptom relief into primary health care: a WHO guide for planners, implementers and managers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

7. Sekse RJT, Hunskår I, Ellingsen S. The nurse’s role in palliative care: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2018;27(1–2):e21–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13912

8. Martins Pereira S, Hernández-Marrero P, Pasman HR, Capelas ML, Larkin P, Francke AL. Nursing education on palliative care across Europe: Results and recommendations from the EAPC Taskforce on preparation for practice in palliative care nursing across the EU based on an online-survey and country reports. Palliative Medicine. 2021;35(1):130–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216320956817

9. Phillips J, Johnston B, McIlfatrick S. Valuing palliative care nursing and extending the reach. Palliative Medicine 2020;34(2):157-159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216319900083

10. Timm H, Thuesen J, Clark D. Rehabilitation and palliative care: histories, dialectics and challenges. Wellcome Open Research. 2021 Jul 2;6:171. https://doi.org/10.12688/Wellcomeopenres.16979.1

11. Sundhedsstyrelsen. Anbefalinger for den palliative indsats. 2011. København.

12. Retsinformation. Bekendtgørelse om uddannelsen til professionsbachelor i sygepleje. BEK nr 804 af 17/06/2016 (Historisk): Bekendtgørelse om uddannelsen til professionsbachelor i sygepleje. 2016.

13. Deravin-Malone, L., Anderson, J., & Croxon, L. Are newly graduated nurses ready to deal with death and dying?—A literature review. Journal of Nursing and Palliative Care. 2016; 1(4), 89–93. https://doi.org/10. 15761/npc.1000123

14. Dobbins, E. H. The impact of end-of-life curriculum content on the attitudes of associate degree nursing students toward death and care of the dying. Teaching and Learning in Nursing. 2011; 6(4), 159–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teln.2011.04.002

15. Zheng R, Lee SF, Bloomer MJ. How new graduate nurses experience patient death: A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2016; 53: 320-330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.09.013

16. Dimoula, M., Kotronoulas, G., Katsaragakis, S., Christou, M., Sgourou, S., & Patiraki, E. Undergraduate nursing students’ knowledge about palliative care and attitudes towards end-of-life care: A three-cohort, cross-sectional survey. Nurse education today. 2019; 74, 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.11.025

17. Zhou, Y., Li, Q., & Zhang, W. Undergraduate nursing students’ knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy regarding palliative care in China: A descriptive correlational study. Nursing open. 2020; 8(1), 343–353. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.635

18. Noer VR. “Rigtige sygeplejersker”. Uddannelsesetnografiske studier af sygeplejestuderendes studieliv og dannelsesprocesser. Københavns Universitet, Det Humanistiske Fakultet.; 2016. 251s.

19. Juul Jensen C. Nyuddannede sygeplejerskers møder med realiteterne på medicinske afsnit i reformerede sygehuse: en institutionel etnografisk undersøgelse. [Roskilde]: Ph.d.-skolen for Mennesker og Teknologi, Roskilde Universitet; 2018.

20. Mousing, CA., Pleth, AT., Adler, M., & Noer, VR. Sygeplejestuderendes parathed og forestillinger om palliative indsatser. Uddannelsesnyt 2022; 33(1), 9-14.

21. Croxon, L., Deravin, L., & Anderson, J. Dealing with end of life—New graduated nurse experiences. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2018 Jan; 27(1-2): 337 – 344. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13907

22. Henoch I, Melin-Johansson C, Bergh I, Strang S, Ek K, Hammarlund K, Lund Hagelin C, Westin L, Österlind J, Browall M. Undergraduate nursing students’ attitudes and preparedness toward caring for dying persons – A longitudinal study. Nurse Education in Practice. 2017;26:12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2017.06.007

23. Österlind J, Prahl C, Westin L, Strang S, Bergh I, Henoch I, et al. Nursing students’ perceptions of caring for dying people, after one year in nursing school. Nurse Education Today [Internet]. 2016;41:12–6. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.03.016

24. Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. 2015.

25. Sandelowski M. Qualitative analysis: What it is and how to begin. Research in Nursing & Health. 1995;18(4):371–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770180411

26. Andersson, E., Salickiene, Z., Rosengren, K. To be involved – A qualitative study of nurses’ experiences of caring for dying patients. Nurse Education Today. 2016; 38:144-149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2015.11.026

27. Martinsen, K. (2012) Løgstrup og sygeplejen. Forlaget KLIM, 2012.

28. Herholdt-Lomholdt, S.M. Misklang mellem sygeplejens sag og fag. I: Et sundhedsvæsen for fremtiden. Sygeplejersker viser vejen. Falch, L.A. & Danbjørg, D.B. (red.). København: Forlaget Samfundslitteratur. 2023, 127-138

29. Martinsen, K. Omsorg, sårbarhet og tid. Klinisk Sygepleje, 2011; 25(4):5-9. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1903-2285-2011-04-02

30. Frögéli E, Rudman A, Ljótsson B, Gustavsson P. Preventing stress-related ill health among newly registered nurses by supporting engagement in proactive behaviors: Development and feasibility testing of a behavior change intervention. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2018;4(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-017-0219-7

31. Berglund M, Kjellsdotter A, Wills J, Johansson A. The best of both worlds – entering the nursing profession with support of a transition programme. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science. 2022;36:446–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.13058

32. Lykke T., Dreyer P. & Mortensen A. Nyuddannede sygeplejerskers frygt for at begå fejl – et kvalitativt interviewstudie. Nordisk Sygeplejeforskning. 2024;14(3):1-13.

33. Benner, P. Fra novice til ekspert. København: Munksgaard. 2013.

34. Nordentoft, H. M. Kollegiale vejledningsformer og læring i sundhedsarbejdet. I: Simovska V & Jensen JM (Red.), Sundhedspædagogik i sundhedsfremme. Gads Forlag, 2012, s. 273.

35. Van Camp J, Chappy S. The Effectiveness of Nurse Residency Programs on Retention: A Systematic Review. AORN Journal. 2017;106(2):128–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aorn.2017.06.003

36. Mellor P, Gregoric C, Atkinson LM, Greenhill JA. A Critical Review of Transition-to-Professional-Practice Programs: Applying a Standard Model of Evaluation. Journal of NursingRegulation. 2017;8(2):23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2155-8256(17)30095-9

37. Ludvigsen MB. Mangel på sygeplejersker giver dårligere kvalitet og lavere patientsikkerhed. Sygeplejersken / Danish Journal of Nursing. 2022; Available at: https://dsr.dk/politik-og-nyheder/nyhed/mangel-paa-sygeplejersker-giver-daarligere-kvalitet-og-lavere

38. Henriksen J, Kristensen IV. At tage små skridt i tilpasset tempo – nyuddannede sygeplejerskers oplevelse af at være i en introduktionsstilling. Klinisk Sygepleje. 2023; Vol.37, Issue 2, pp. 71-87. https://doi.org/10.18261/ks.37.2.2

Vil du være opdateret med faglig udvikling, forskning og viden, kan du tilmelde dig nyhedsbrev her og måske blive den heldige vinder af månedens T-shirt.