Children with tracheostomy: A qualitative exploration of parent’s experiences and needs

Tanja Østergaard Irlind, MPH, clinical nursespecialist RN 1

Camilla Grauslund Bredahl, MSc, headnurse, RN 2

Ingelise Hvidt, MSc, clinical nursespecialist RN 2

Mona Ring Gätke, MD, phD 1

Lone Graff Stensballe, professor, MD, phD 2, 3

1 Denmark Department of Respiratory Center East, Copenhagen University Hospital, Denmark

2 The Child and Adolescent Clinic, The Danish National University Hospital,

3 Department of Clinical Medicine, University of Copenhagen

Abstract

Background. The number of children aged 0-15 with tracheostomies is increasing, and their treatment processes are complex. Research indicates significant negative consequences for families with a child with a tracheostomy. The purpose of this study was to explore parents’ experiences and needs from the decision about the tracheostomy to life at home.

Methods. Data were collected in Eastern Denmark, where semi-structured interviews were conducted individually or in dyads with 13 parents of seven children with tracheostomies, who are associated with the respiratory center in the Capital Region. A qualitative descriptive method was used, and the empirical data were analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results. Seven themes emerged: 1. The child with a tracheostomy: Prioritizing the child’s needs and well-being. 2. Communication: Lack of information and shared decision-making. 3. The treatment process: Lack of parental involvement in the treatment process. 4. Transitions between units: Lack of coordination and collaboration between units. 5. Navigator: The treatment process requires a navigator. 6. Trained personal caregivers: An intrusion into privacy. 7. The Family: The relationship, siblings, and relatives are under pressure.

Conclusion. This study provides valuable insights into parents’ experiences with tracheostomy care for children in Eastern Denmark. Parents of children with tracheostomies seek clear information and involvement. They face challenges throughout the treatment process, as well as after discharge from the hospital. Parents often feel stressed by the trained personal caregiver arrangement and seek more flexibility and support. There is a need for support for family well-being and planning of treatment and care. Further research is necessary to deepen the understanding of this complex treatment environment and to identify effective intervention strategies.

Clinical relevance. This study highlights the clinical relevance of understanding parents’ experiences and needs regarding children with a tracheostomy, a subject with significant implications for the entire family. The study identifies areas where guidelines and interventions could be developed to improve nursing care and clinical practice in supporting families with a child who has a tracheostomy.

Keywords. Parents, children, experiences, needs, tracheostomy, pediatric, tPCG

Abbreviations

Trained Personal Caregiver = tPCG: When a person with a tracheostomy in Denmark cannot manage their own care, or if the patient is a child, they are assigned a team of 6-8 tPCGs. This team is trained and certified by a respiratory center; some caregivers have a healthcare background, such as nursing or social and healthcare assistant, while others come from entirely different fields. While the patient is hospitalized, the tPCG are trained in the specific care tasks they will perform at home after discharge. Their responsibility is limited to respiratory care and treatment, but in certain cases, the municipality can delegate additional tasks, provided they do not interfere with their primary responsibilities.

Invasive treatment: Ventilation treatment with a tracheostomy tube. Noninvasive treatment: Ventilation treatment with a mask.

Introduction

The prevalence of tracheostomies in children aged 0-15 years is increasing, as more children with severe neuromuscular disorders, congenital anomalies, prematurity, and malignancies are surviving (1–6). The complex and prolonged treatment processes give rise to significant challenges (2–4). Tracheostomy procedures are typically performed in children with upper airway anomalies, chronic neurological and respiratory disorders, or those who require long-term mechanical ventilation (1,5–7). Potential risks associated with tracheostomies include airway obstruction, secretions stagnation, tube displacement, bleeding, and infection, which, in the worst cases, can result in respiratory arrest (5,8). International guidelines and practices for the observation, treatment, and care of children with tracheostomies vary significantly. In Denmark, families have access to a team of tPCGs, where tPCGs, employed by private staffing agencies, collaborate with respiratory centers to provide the necessary monitoring and care.

Danish legislation establishes clear guidelines that the tPCG must always be within sight and hearing distance (9). However, parents have the option to waive this requirement and assume partial or full responsibility themselves. Parents’ management and experiences in caring for a child with a tracheostomy vary significantly (10). In Denmark, the treatment process for children with tracheostomy is initiated at specialized hospitals like Rigshospitalet. However, there is often a lack of a coordinator in these processes, which can lead to uncertainty and vulnerability for the families. Furthermore, studies indicate that families with disabled children are at an increased risk of serious negative consequences such as divorce, job loss, and siblings becoming “shadow children.”(11,12). A tPCG at home, taking care of a child’s tracheostomy changes the family’s life and can be challenging.

It is important to align expectations to minimize potential issues in the collaboration between the family and the tPCG. (10,11,13,14). From 2015 to 2020, Rigshospitalet treated 15 children and adolescents aged 0-17 years with tracheostomy. The diagnosis and treatment of underlying conditions take place in the pediatric departments, while ventilator treatment, training, and certification of tPCGs are conducted at the hospital’s respiratory treatment center. However, there is a lack of qualitative research that explores parents’ long-term experiences with caring for a child with a tracheostomy. (8). A previous study conducted by Flynn et al. in 2013(8) focused exclusively on parents who were solely responsible for the observation and care of their child, without providing insight into the parents’ experiences with the tPCG arrangement that is implemented in Denmark.

Aim

This study aimed to explore parents’ experiences and needs throughout the process, from the decision-making regarding a child’s tracheostomy to life at home afterward, within a Danish context where a tPCG arrangement is established.

Method

Design

In this study, a qualitative descriptive method was used, employing individual or dyadic interviews (15) with parents of children residing in Eastern Denmark who had undergone tracheostomy procedures.

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the department management, and the study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (16). Data is stored on a secure closed server. All participants were made anonymous during transcription and given a number for the child and a M for mother or F for father.Before participation, all participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

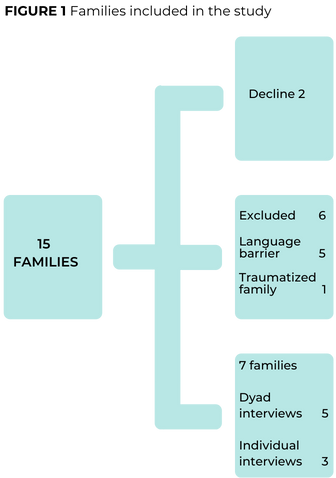

All parents of the 15 children who had undergone tracheostomy procedures within the previous five years were invited to participate. This five-year timeframe was chosen to reduce potential recall bias. 13 parents, representing seven children with tracheostomy, were recruited for the study (see Figure 1). One parent was unable to participate on the scheduled interview day and declined to arrange a new date. Two pairs of parents declined to participate: one pair could not fit an interview into their busy schedule, while the other pair did not want to revisit the period by recounting and discussing it. Five families were excluded due to language barriers, and one family was deemed by the research team to be too traumatized to participate (see Figure 1).

Inclusion criteria:

- Parents of children who are alive and between the ages of 0-18.

- Ability to understand and speak Danish.

- Contact with the hospital within the past five years.

- The child has had or currently have a team of tPCGs within the last five years.

- The child has had or currently has a tracheostomy within the last five years.

Data collection

The semi-structured interviews were conducted between July 2020 and April 2021. Our interview guide was piloted and revised after the first interview. Four researchers conducted separate interviews to ensure that both participating departments were equally represented in the data collection. The advantages and disadvantages of having four interviewers were discussed within the research team, and it was found that the benefits outweighed any potential drawbacks. The interviews lasted between 24 and 104 minutes (averaging 66 minutes), were recorded, and professionally transcribed verbatim using the software program Express Scribe. It was encouraged that both parents be present if they lived together, to ensure that both parents’ perspectives were represented as fully as possible. Since the researchers found that parents shared their individual experiences and needs during the dyadic interviews, there were no concerns about whether participants felt they could be completely honest, a topic previously discussed within the research team. All children were too young to participate. In total, eight interviews were conducted: five dyadic interviews, were both parents participated at the same time and three individual interviews, all held in the children’s homes (see Figure 1).

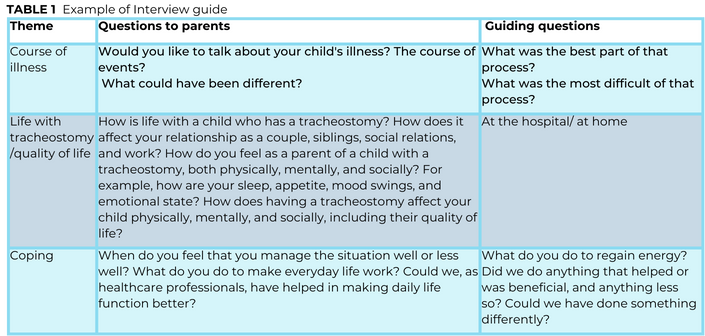

Participants were asked open-ended questions according to an interview guide with 10 topics: needs, coping, collaboration, knowledge, respiratory caregiver team, transitions between units, parental role, disease progression, quality of life, and patient journey. The interview guide was developed based on existing literature and knowledge from healthcare professionals who work with children with tracheostomy daily. See Table 1 example of interview guide.

Analysis

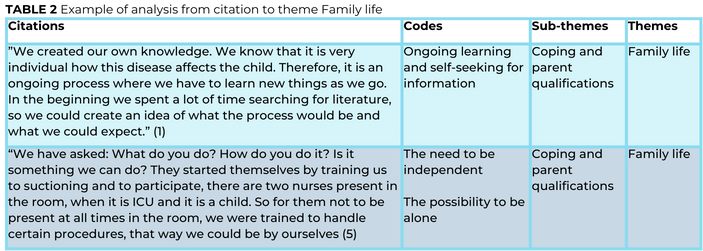

The interviews were analyzed inductively using Braun and Clarke’s method for qualitative thematic analysis (17) . This method is well-suited for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within the data (see Table 2).

The analysis followed six steps:

1. reviewing the data

2. generating initial codes

3. searching for themes and sub-themes

4. reviewing themes

5. defining and naming themes and sub-themes. 6. consensus on the final themes, definitions, and naming was achieved among all researchers (17).

Results

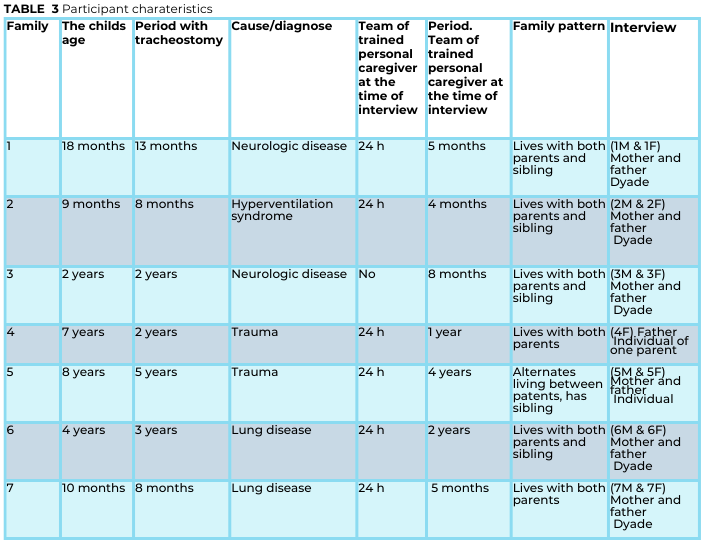

A total of 15 eligible families were identified, of which seven families agreed to participate in the study, as shown in Figure 1. At the time of data collection, the children’s ages ranged from nine months to eight years. The durations for which the children had had a tracheostomy ranged from eight months to five years. Additionally, there were various reasons for the children having received a tracheostomy, which is illustrated in Table 3.

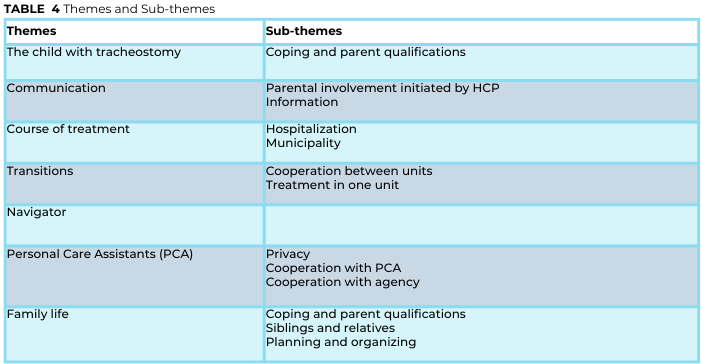

Seven themes and their sub-themes were identified as being of utmost significance for families with a child who has a tracheostomy (see Table 4).

The child with a tracheostomy

The child’s well-being and development are important to all the parents. As one parent expressed:

“I fight to get that wheelchair everywhere so he can see what he wants, and I just try to be a normal family without focusing too much on the fact that he has a tracheostomy. It has to be a secondary thing. It’s there, it works, and it works well, so we just accept that this is the premise for us” (5/F).

The quote illustrates that parents want their child to experience and have as normal a life as possible, given the child’s conditions and limitations.

Communication

All the parents expect respectful communication with healthcare professionals and between healthcare professionals and tPCGs, both in the hospital and at home.

Involvement & Information

The majority of the parents emphasize the importance of healthcare staff actively listening to them and respecting and recognizing their expertise as parents and caregivers. They want to be involved in the care process and advocate for shared decision-making, although this is not always consistently practiced. Parents observe varying attitudes towards their involvement and the level of support from healthcare professionals. Some parents report a lack of information and uncertainty about expectations during their hospital stay. They stress the need for clear plans and instructions. Parents express that knowledge is crucial for improving their coping skills and facilitating preparation for discharge from the hospital.

They also describe difficulties in remembering and understanding information, as illustrated by one parent who said:

“I have asked for a summary of our conversation because I can’t remember everything that is said. Then you have it on paper and can say: Okay, that wasn’t quite right, or something like that” (7/M).

The quote underscores the importance of written materials and the use of clear, understandable language by healthcare professionals. Parents express a need for easily accessible hospital contact and regular telephone follow-ups concerning their child’s physiological, social, mental, and cognitive well-being. This would provide parents with reassurance and peace of mind. They receive a large amount of information in a very short time, so written information would allow them to review or repeat the information to family members later.

Treatment Process

Three pair of parents describe the treatment process as mentally challenging and report experiencing stress and a negatively impacted quality of life. One parent describes:

“I went to see a psychologist, and you felt so unwell… you had pain, not from anything other than feeling unwell. It was stress…” (1/M).

If parents experience an inadequate treatment or diagnostic process, it will leave them with frustration and uncertainty, which impacts the subsequent course of care. Parents may feel uncertain if they perceive that healthcare professionals are not prepared to receive the family with a clear plan or lack experience and confidence in pediatrics. Some parents feel frustrated and resistant towards healthcare professionals if there is a lack of flexibility in rules and procedures. One father recount:

“It was not at all adapted for families with children. They told us how it should be done, and it provoked us a lot. We had managed fine for several months” (1/F).

Municipality

The municipality is involved in the assistance that families receive at home, but some parents may feel that the municipality does not fully understand their child’s disability and needs. Some parents are not included in decisions about the type of support their child receives, which creates feelings of desperation and hopelessness. Some parents find the system challenging and spend significant energy and time ensuring their rights. They seek help from the hospital’s social worker and need a “navigator”(18) to effectively navigate this process (see “navigator” below).

Transitions & Collaboration between units

All the parents describe transitions as challenging, both between different hospital departments and from the hospital to home. To promote feelings of security, independence, and coping, parents advocate for support and practical assistance during the transition to home. Frustrations can be minimized during transitions between units through thorough preparation and alignment of expectations with parents. It is important to prevent misinformation by ensuring that collaborating healthcare professionals do not speak on behalf of one another. All the parents emphasize that healthcare professionals’ knowledge of the child, the illness, the overall treatment process, and the competence of the staff across all medical specialties fosters trust and reassurance. They express a preference for receiving centralized care to avoid fragmentation. Two pair of parents experience a lack of collaboration between hospital departments and between the hospital and the municipality. When inter-unit collaboration does not function smoothly, parents find that treatment and care are negatively affected, leading to uncertainty and anxiety. One mother reports her experience, when collaboration between units is perceived as problematic:

“There were several people who had problems with each other and had difficulty collaborating, which became our problem. There is a lot of negativities and a poor atmosphere that affects our treatment process” (1/M).

This cote shows important and crucial coordination, agreements on guidelines, and parents’ training programs are for preventing frustrations. Three pair of parents express a preference of centralized care to avoid multiple consultations, save time, and ensure that healthcare professionals have adequate knowledge.

Navigator

The parents are responsible for coordinating their child’s treatment and communication between healthcare professionals, which leaves them feeling overwhelmed due to the enormous responsibility. They also express a sense of not knowing about available resources and options, which adds to the challenges and burdens they experience. All the parents seek help to navigate and coordinate their child’s care and treatment pathway in the healthcare and municipality system, a healthcare professional, a navigator, whom has knowledge about their rights and needs as a family.

Trained personal caregiver

To have a team of trained personal caregivers 24 hours a day is perceived by all parents as challenging. Those challenge will be elaborated in the following sections.

Privacy

For all of the families, it is mentally stressful that the respiratory caregivers are strangers and present day and night. It is perceived as intrusive to their privacy, as one father describes:

“It affects me a lot. Sometimes it’s okay, other times I just think it’s absolutely terrible” (1/F).

Parents are aware that they are being observed, which makes them hesitant in their natural parenting roles due to concerns about what tPCGs might think. The majority of parents find it crucial for the family’s well-being to have time alone without the tPCG and therefore desire more flexibility to use the help only when necessary. They also want flexibility regarding the tasks the tPCG performs, beyond the respiratory duties.

Collaboration with the trained personal caregiver and the agency

All patents express that having a team of tPCGs is both a challenge and a relief, requiring focus on collaboration between the family and the tPCGs. Successful collaboration depends on clear communication of expectations and agreements that build trust and strengthen the relationship, as one father explains:

“To make it work, they need some rules; otherwise, it just won’t work” (5/F).

A lack of qualifications in the tPCG creates concerns for both the child and the parents. Entrusting the responsibility of the child to the caregiver is difficult, and some parents do not want the tPCG to assume parenting responsibilities. There are instances of inappropriate behavior from tPCGs, including yelling or reprimanding, which does not take the child’s needs into account. To establish a positive relationship with the tPCGs, some parents seek support from healthcare professionals and written information about guidelines and requirements for caregivers in the home. Overall, parents experience poor collaboration with the agencies where the tPCGs are employed, noting a lack of involvement in making decisions, empathy, commitment, and flexibility from the agency. Parents call for better communication.

Family life

Coping and parental skills

The majority of parents experience constant concern for their child with a tracheostomy, which requires ongoing monitoring. Children with tracheostomies have many needs, and the parents’ responsibilities are enormous, the parents varying in how they manage the situation. Coping strategies for parents include family time without tPCGs, social activities with friends, and support from other parents in similar situations. Support from relatives and psychological support are also valued. Additionally, the parents in our study seek skills to manage treatment and care independently. One mother describes:

“The more we do ourselves, the happier we are; the more you can do without the respiratory caregiver”(1/M).

For all the parents these skills provide a meaningful role, control, and greater flexibility in the use of respiratory caregivers, which is crucial for the family’s quality of life and well-being.

Relationship with Partner

The majority of the parents find that their relationship with their partner is challenged due to a lack of time, competing priorities, increased burden of daily responsibilities, and reduced privacy. All the parents emphasize the importance of planning between partners, taking breaks away from home, and maintaining open communication as crucial factors for nurturing the relationship.

Siblings and Relatives

In the five families where there are siblings, the study showed that siblings react differently to changes in daily routines, new routines, and new people. Some do not react to the presence of the tPCG, while others prefer not to be around them. All five pair of parents advocate for support for siblings from institutions, psychologists, and family counselors. Some siblings take on too much responsibility for monitoring the sick child, and hospitalizations negatively affect some siblings, as one mother describes:

“We received help on how to handle her when she [sister] was upset or angry. She developed obsessive-compulsive tendencies to control herself, but she no longer does that” (2/M).

For all the families, relatives play a crucial role in supporting parents by providing respite, assisting with practical tasks, and caring for the child. However, this requires adequate information and training of the relatives in the respiratory care. Currently, there are no clear guidelines for training relatives, which leads some parents to take on the responsibility of training the relatives themselves.

Planning and Organization

Having a child with a tracheostomy means more work than usual; planning and organizing treatment and care become central, which many parents describe as stressful. One father recount:

“The project is to make everything work, especially with X [child number 4], the tPCG, who sleeps where, who does what, who do we call at night” (4/F).

Therefore, the compensation offered by the Danish state for a parent to stay home which all families receive, is valuable. There is a large amount of medical equipment that complicates activities outside the home; it takes time and is inflexible. Some parents experience their home becoming hospital-like, and it is important to set boundaries for medical equipment and the tPCG in the home.

Discussion

This qualitative study was conducted in Eastern Denmark with the aim of optimizing treatment pathways by incorporating information on parents’ perspectives. Through semi-structured interviews with 13 parents of seven children with tracheostomy, key themes within parental experiences and needs were identified. The study indicates that the treatment focus for children with tracheostomy is primarily directed towards physical health and survival. However, our main findings underscore the need to prioritize psychosocial health, as parents report affected quality of life, stress, challenges in receiving daily assistance, and mental health issues in siblings.

The results confirm previous Danish studies, particularly Alrø et al. from 2019, but this study differs by focusing solely on children with invasive treatment, while the previous study included both invasive and non-invasive treatments. This distinction is relevant regarding the extent of need for tPCGs, as non-invasive treatment only requires monitoring during treatment (while sleeping/at night), whereas invasive treatment necessitates constant 24/7 monitoring. These differences may impact parents’ experiences and needs, as discussed in Bjerregaard Alrø et al.’s study (10). Several studies show (19,20) , that children and adolescents after life-threatening illnesses face challenges in four health areas: Social, mental, cognitive and physical. This study contributes to the discussion on the need for increased focus on these four areas, particularly in relation to families with children who have a tracheostomy.

The parents in this study emphasize the importance of smooth transitions between units, where the child’s care remains consistent, and procedures and information about care are well-coordinated. Reassurance is achieved through well-organized transitions, supportive communication between units, and respect for parents’ expertise from previous units. This is supported by other studies, which show that transitions between units can be stressful for both parents and the child, as it involves building new relationships with staff who do not have the same in-depth knowledge of the child as the previous staff. (21,22).

Parents may experience fatigue due to changing staff during a prolonged hospital stay. (22) . A study by Abode et al. (23) indicates that centralization can optimize hospitalization and prevent complications associated with tracheostomy. Our study also shows that having a child with a tracheostomy requires extensive contact with various units, placing demands on parents for planning and resources. Parents describe it as stressful and frustrating to experience difficulties in obtaining necessary assistance, supporting the findings of Flynn et al. (8).

Our findings reveal a significant need for a Navigator (18) whom parents can turn to for help and who can ensure seamless transitions between units. Other studies have also highlighted the need for a family navigator nurse in the patient pathway (18,24). Our results show that parents want to be actively involved in their child’s treatment and care, and to gain competencies early in the treatment process. Research indicates that increased parental knowledge and skills, resulting from involvement, have positive effects on the child’s health. (25–29) . When parents are given the opportunity to take an independent role in the respiratory treatment and care, they can have family time without respiratory helpers, which is desired by the parents in our study. Parents also wish for flexibility regarding the presence of help during the day, which aligns with findings from other studies (10). By involving and informing parents in the training of respiratory helpers at the hospital, parents can gain insight into the reasons for any delays or changes, thereby preventing some of the frustrations they express in our study.

Methodological considerations

As the data collection period extended over 12 months, there is a risk that researchers may have inadvertently influenced the environment by making minor adjustments based on insights gained from interviews. Additionally, there is potential for information bias (30), as participants continued to interact with our units and might withhold certain information to maintain positive relationships. The study participants were parents of children with various diagnoses and ages at which the tracheostomy and respiratory support were initiated. This diversity is a strength for our conclusions, as the broad range of participant backgrounds provided varied but consistent experiences. Interviews were conducted by multiple researchers, which could be a limitation due to potential differences in interview execution and interpretation. To mitigate these limitations, steps were taken to ensure consistency and rigor in the research process, including detailed training for interviewers and regular team discussions to align on methodological approaches.

Conclusion

The findings from this study indicate that parents of children with tracheostomies require respectful communication, clear information, and involvement in their child’s care. Parents face challenges with treatment processes, hospital stays, municipal services, and inter-unit collaboration. Families often feel overlooked and stressed by respiratory care providers and need more flexibility and support. The study highlights that parents need support for family well-being and the planning of treatment and care. Overall, parents seek improved coordination and communication to ensure optimal care and well-being for their child and family.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank all participants for their participation in this project.

References

1. Parker V, Shylan G, Archer W, McMullen P, Morrison J, Austin N. Trends and challenges in the management of tracheostomy in older people: the need for a multidisciplinary team approach. Contemporary nurse. 2007;26(2):177-83.

2. McPherson ML, Shekerdemian L, Goldsworthy M, Minard CG, Nelson CS, Stein F, et al. A decade of pediatric tracheostomies: Indications, outcomes, and long-term prognosis. Pediatric pulmonology. 2017;52(7):946-53.

3. Gronhoj C, Charabi B, Buchwald CV, Hjuler T. Indications, risk of lower airway infection, and complications to pediatric tracheotomy: report from a tertiary referral center. Acta oto-laryngologica. 2017;137(8):868-71.

4. Resen MS, Grønhøj C, Hjuler T. National changes in pediatric tracheotomy epidemiology during 36 years. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275(3):803-8.

5. Carron JD, Derkay CS, Strope GL, Nosonchuk JE, Darrow DH. Pediatric tracheotomies: changing indications and outcomes. The Laryngoscope. 2000;110(7):1099-104.

6. Watters KF. Tracheostomy in Infants and Children. Respir Care. 2017;62(6):799-825.

7. Crumpton J, Wray J. Children’s and adolescents’ experiences of living with respiratory assistance: A systematic review of qualitative studies. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2019;127:109658.

8. Ali SO, Yeung T, McKeon M, Maddock M, Graham RJ, Nuss R, et al. Patient and caregiver experiences at a Multidisciplinary Tracheostomy Clinic. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2020;137:110250.

9. Flynn AP, Carter B, Bray L, Donne AJ. Parents’ experiences and views of caring for a child with a tracheostomy: a literature review. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2013;77(10):1630-4.

10. Bjerregaard Alrø A, Klitnaes C, Dahl Rossau C, Dreyer P. Living as a family with a child on home mechanical ventilation and personal care assistants-A burdensome impact on family life. Nursing open. 2021.

11. Lindahl B, Kirk S. When technology enters the home – a systematic and integrative review examining the influence of technology on the meaning of home. Scandinavian journal of caring sciences. 2019;33(1):43-56.

12. Lindahl B, Lidén E, Lindblad B-M. A meta-synthesis describing the relationships between patients, informal caregivers and health professionals in home-care settings: Caring or being cared for at home. Journal of clinical nursing. 2011;20(3-4):454-63.

13. Loft LTG. Child Health and Parental Relationships: Examining Relationship Termination Among Danish Parents with and Without a Child With Disabilities or Chronic Illness. International Journal of Sociology. 2011;41(1):27-47.

14. Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Interview : introduktion til et håndværk. 2. udgave. ed. Kbh: Hans Reitzel; 2011.

16. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology. 2006;3(2):77-101.

17. Yin HS, Sanders LM, Rothman RL, Shustak R, Eden SK, Shintani A, et al. Parent health literacy and “obesogenic” feeding and physical activity-related infant care behaviors. J Pediatr. 2014;164(3):577-83.e1.

18. Harrington KF, Zhang B, Magruder T, Bailey WC, Gerald LB. The Impact of Parent’s Health Literacy on Pediatric Asthma Outcomes. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol. 2015;28(1):20-6.

19. Kristensson-Hallström I. Strategies for feeling secure influence parents’ participation in care. J Clin Nurs. 1999;8(5):586-92.

20. Jones DC. Effect of parental participation on hospitalized child behavior. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 1994;17(2):81-92.

21. Liechty JM, Saltzman JA, Musaad SM. Health literacy and parent attitudes about weight control for children. Appetite. 2015;91:200-8.

22. Mikkelsen G, Frederiksen K. Family-centred care of children in hospital – a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(5):1152-62.

23. Hutchfield K. Family-centred care: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 1999;29(5):1178-8

24. Suleman Z, Evans C, Manning JC. Parents’ and carers’ experiences of transition and aftercare following a child’s discharge from a paediatric intensive care unit to an in-patient ward setting: A qualitative systematic review. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2019;51:35-44.

25. Abode KA, Drake AF, Zdanski CJ, Retsch-Bogart GZ, Gee AB, Noah TL. A Multidisciplinary Children’s Airway Center: Impact on the Care of Patients With Tracheostomy. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2):e20150455.

26. Chaiyakulsil C, Opasatian R, Tippayawong P. Pediatric postintensive care syndrome: high burden and a gap in evaluation tools for limited-resource settings. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2021;64(9):436-42.

27. Manning JC, Pinto NP, Rennick JE, Colville G, Curley MAQ. Conceptualizing Post Intensive Care Syndrome in Children-The PICS-p Framework. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19(4):298-300.

28. Johnson M, Jefferies D, Nicholls D. Exploring the structure and organization of information within nursing clinical handovers. International journal of nursing practice. 2012-10. vol 18. p. 462-470

29. Herbst LA, et al. Going back to the ward-transitioning care back to the ward team. Translational pediatrics, 2018-10.vol 7 p. 314-325

30. Baekgaard H. The effects of a controlled family navigator nurse: directed intervention program for parents hospitalized with children undergoing allogeneic haematopoitic stem cell transplantation (HSCT): Ph.D. dissertation 2011.

Vil du være opdateret med faglig udvikling, forskning og viden, kan du tilmelde dig nyhedsbrev her og måske blive den heldige vinder af månedens T-shirt.